Catherine OpieIcehouses

Divided in its union – the desires and contradictions of the American landscape.

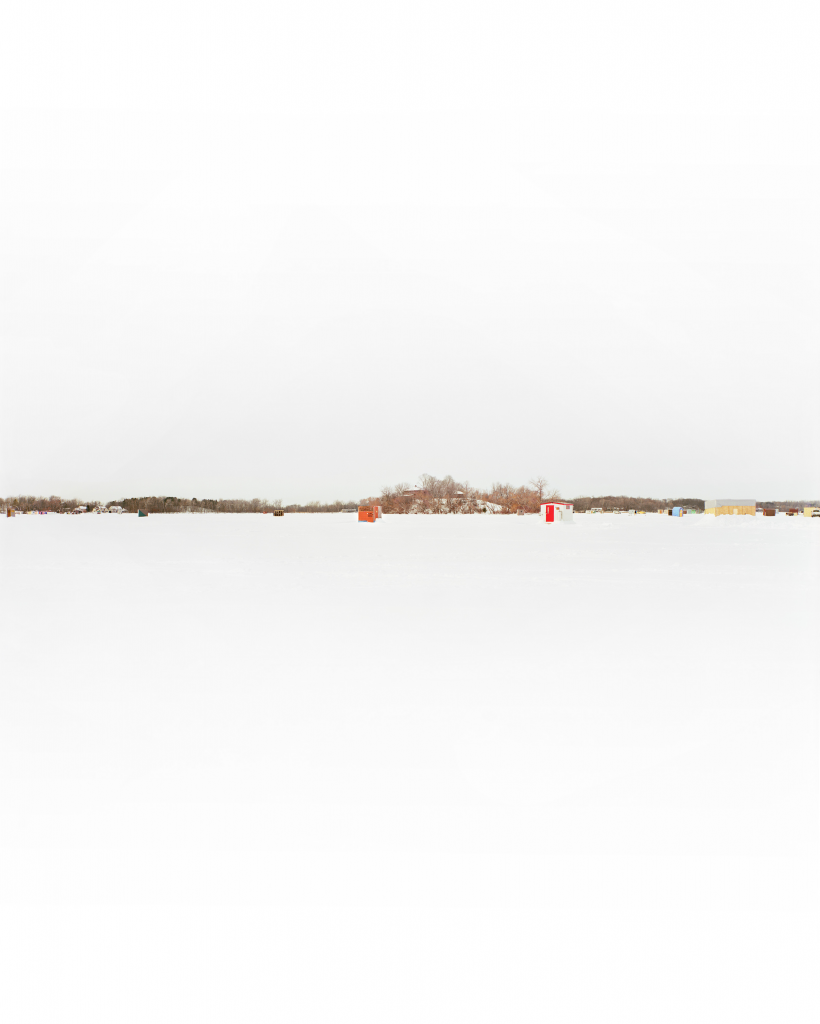

The untitled photographs in Catherine Opie’s 2001 series Icehouses are meditative, nearly monochromatic compositions depicting a scattering of makeshift ice-fishing shelters on a frozen lake in Minnesota’s cold back country. Each of the series’ fourteen large-format colour photographs portrays a snow-bound shore, a modest skyline of bare trees and a sprinkling of toy-like shacks, doors firmly shut against the cold and wind. Adrift in a blinding sheet of white, hovering midway up the picture plane, a gauzy ribbon of horizon where frozen lake merges with snow-bleached sky appears. In some images the icehouses are closer, asserting themselves matter-of-factly: simple geometric structures in bright fairground colours scattered across a blank canvas. In others they recede into the frozen mist, standing as small indistinct objects barely visible behind swirling veils of snow. These are scenes of eerie yet alluring absence. An all-consuming brilliance erases every difference in a homogenous mantle of white, the skyline a mere smudge across a blank empty page. Spending hours outdoors with her 8×10 camera braving frostbite and frozen film in blizzard conditions, Opie captured these understated, hauntingly seductive landscapes during her year-long residency at the Walker Art center in Minneapolis.

“I love the idea that the icehouses are a temporary community. They exist on the ice for only about two months but they receive pizza deliveries, even prostitutes”¹, says the artist. In this transient world which appears and disappears organically with the ice, strangers from very different social strata can form unexpected bonds. The frozen lake is public space – everyone is free to erect their hut wherever they please – yet the icehouses shelter private worlds replete with individual histories, memories, dreams. Underlining this sense of belonging and personal identity, the catalogue from the series’ original exhibition features texts from Minnesota residents recounting their own personal associations with this particular locale. Their short pieces provide a poignant human counterpoint to the empty landscape, animating it with personal anecdotes, memories and poems based on bursts of shared family activity or moments of protracted calm, of setting up camp and of quiet anticipation, waiting for fish to bite.

thus, our position telescopes, tantalisingly, between immediate, human materiality and remote, ethereal nature of its environment. In these images, each tiny structure strikes a primary and resonantly human note, offering the promise of sustenance and shelter, of comforting and familiar detail, against the immutable and silent, all-enveloping landscape. Yet in every image, the photographer is positioned outside, in the deserted void. “Many of [my] house photographs are about the closed door… It is so weird because I never did this purposefully but all of my work of places are vacant of people…” From her earliest well-known self-portrait, of her own naked back bloodily incised with a child-like doodle of a female couple holding hands in front of a cosy home, one can read in Opie’s oeuvre a desire for the domestic, to come inside. Yet the world outside beckons irresistibly, even in the arctic conditions of a bone-chilling Minnesota winter. Bathed in diffused light filtering through the hazy frozen mist, the outside offers its own uncanny comforts and spiritual peace, belying the frigid conditions and harsh isolation endured by the photographer in pursuit of these meditative, dream-like images.

Catherine Opie’s whole body of work is in a constant state of push and pull between these two contradictory poles of human desire. She is equally at home conversing with the sublime as with the domestic and moves regularly from the inside to the outside and back again. Exploring the competing human needs for community and for isolation, her work also probes the iconic but conflicting American dreams of home and mobility. Thus the desire for family and security, for the home behind the white picket fence, conflicts with the desire for the mythical freedom of the open land: the pioneering spirit that is still at the heart of the nation’s identity, culture and character. She has criss-crossed the country and fittingly, as someone who has lived most of her life in Southern California, loves her car. “I’ve had a car since the age of 16 and to me, the freeways always represented this wonderful freedom…”² On the way, she has photographed the backdrops of American lives: intimate domestic interiors but also freeways, tract homes and master-planned suburban developments, downtown financial centres, the gaudy facades of Beverly Hills homes, the local Southern Californian mini-malls that provide a hub for recently arrived immigrant groups. There is a romantic Ansel Adams-like quality to all of Opie’s landscapes. Even her flowing and sculptural freeways are inspirational: abstract and perfectly composed, they make one long for the road rather than decry any blight on the landscape.

Douglas Fogle has written that Opie’s entire artistic career can be seen as “one long road trip across the continent in search not of the American dream but rather a dream of an idea of American community”³. Through regional landscapes and individual portraiture, using different photographic formats and media, she has documented the supposed liberty offered by the physical infrastructures of the nation as well as the more elusive freedom for self expression and identity embodied in the alternative communities she images. She is known as much for her portraits of members of fringe subcultures – it was her unflinching depictions of her own leatherdyke community that first brought her to prominence – as she is now for the unpopulated images of the environments she encounters, exploring architectural vernaculars and probing the semiotics of her surroundings. Visually compelling and formally composed, her images document individuals but also the contexts that shape and reflect them: cultural portraits, on micro and macro scales, of a very diverse nation. Her images are part of a thoroughly humanist tradition, always tender and respectful, capturing with dignity the souls of people and communities whose identities are based as much on broadly shared dreams as on uniquely individual desires.

¹ Catherine Opie as quoted by Hunter Drohojowska-Phlip, ‘For Her, It’s Always About Community’, Los Angeles Times, May 12, 2002, 54

² Catherine Opie, as quoted by Mimi Zeiger, ‘Pro%le: Catherine Opie’, Loud Paper, Vol. 2, Issue 3, 1998, 17

³ Douglas Fogle, Catherine Opie: ‘Skyways and Icehouses’, catalogue to the exhibition at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, April 28 – July 21, 2002, 4