Magali NougarèBlue Skies and Handbags

“The sky is flesh. The great blue belly arches up above the water and bends down behind the horizon. It’s a sight that has exhausted its magnificence for me over the years, but now I seem to be seeing it for the first time.’’¹

At first glance the photographs that makeup Magali Nougarède’s series Toeing The Line appear to be inhabiting familiar photographic territory, playing on our recollections of others who have photographed the seaside as well as beckoning the ghosts of every holiday maker’s photograph album. 1968, Margate, Kent: two little girls, one slender, one plump. Both are wearing almost identical blue dresses covered with big pastel flowers, one is wearing a pointy, wide-brimmed straw hat. Hands behind their backs, little-girl-bellies sticking out, they face the camera, squinting into the bright sunlight. At their feet lie wooden handled spades and one plastic bucket. Above them, the sky is a demanding and brilliant pale grey.² We all think we know what a seaside picture should look like. Its many versions are almost written in stone; only in our heads though, and only if we narrow our vision.

Toeing The Line is both a meditation on and a mediation between the spaces of the concrete world and the private spaces of self. In her previous work from the series Breaking Surface (1996) and Trial by Fire (1998), Magali Nougarède explored mental states through the metaphoric use of the elements water and fire. In this new body of work, she explores this idea of metaphor further. By focusing tightly upon women and capturing the quality of light that exists on a day like that which Martin Amis calls “…one of the most beautiful days of this or any other year. A faultless morning, a blue-planet afternoon…”³, Nougarède presents us with a view of Eastbourne as a place full of genteel elderly women and young girls. It is a gentle, subtle view, without satire or irony, that also begins to question the expectations and rigidity of middle-class assumptions and conformity, especially those which impact on women. To ‘toe the line’ is to conform, to accept wholeheartedly the values that are handed down from one’s parents and society in general. To ‘toe the line’ is to not rebel. It is as though Nougarède is presenting a world to us that she knows intimately a world which she has left behind, yet feels the resonances of still.

In her introduction to French Provincial Cooking, Elizabeth David says of a book she found in a market in Toulouse “…The book exudes an atmosphere of provincial life which appears orderly and calm whatever ferocious dramas may be seething under the surface…”⁴

Nougarède is encouraging us to go beyond the surface of our cultural assumptions, beyond the nostalgic, sentimentalised attitudes we hold. She is asking us to see what is beneath, both within the images she has created and within ourselves. The dramas that she is prompting us to recognise are those of our inner world. They may not always be passionately dramatic. They may be quiet and still and slow. Our coming to consciousness and our awakening to change happens in many forms and many times throughout our lives.

By focusing on the minutiae of the everyday, Nougarède’s images narrate not only the passage of her walks through the very particular landscape of Eastbourne, but also allow us to glimpse the possibility of the “…ferocious dramas…” to which Elizabeth David refers. Her photographic technique, the use of flash in bright sunlight, only goes to heighten the theatricality of the light and to outline more sharply her subjects. The never-ending blue of her images serves as a backdrop against which the lives of girls and women are played out. We are shown the passage of everywoman at particular times of transformation; the child, the adolescent, the old woman. The young woman, in her 30s, is present only behind the camera. Although located firmly within a particular landscape, these images also stand alone as a more personal and particular view of psychological spaces, speaking of thresholds closely linked with age. Somehow the extremes of old age and childhood that are brought to us in this body of work mirror the way that both we as outsiders and the inhabitants of Eastbourne see the town itself. The received stereotypical reputation of the town is of a South coast resort that has a strong sense of its seaside Englishness, with its true-blue Tory affluence and its population of retired middle-class couples. When you think of Eastbourne you do not think of young people. Both the Eastbourne Herald and the Eastbourne Gazette see a need to balance this perception, for each week they publish a supplement devoted to recent Eastbourne new-borns. The big issues of birth and death are always present for us, as are the smaller, personal, inner births and deaths of our psychological lives. In Toeing The Line we are being quietly nudged towards contemplating them.

These images mobilise our inner lives and open us up to new ways of seeing. Nougarède could be said to have made a series of iconic images of women at stereotypically, recognised times of life. Women of her own age are not present, and it is as if she is somehow looking both forwards and backwards for signposts to which she can relate. The contemplation of our own mortality, of what we are about to make of our lives is always with us, but perhaps never so strongly as when we are in our early thirties. The age of thirty is a crossroads that brings complex questions for both men and women, but perhaps more so for women questions about creativity in the form of career and motherhood. It is often a time where confidence and character, the ability to go out into the world and to feel comfortable with oneself are in synchronisation. It is a space where there is, hopefully, more time in front of us than behind.

“Blue protects white from innocence Blue drags black with it Blue is darkness made visible.”⁵

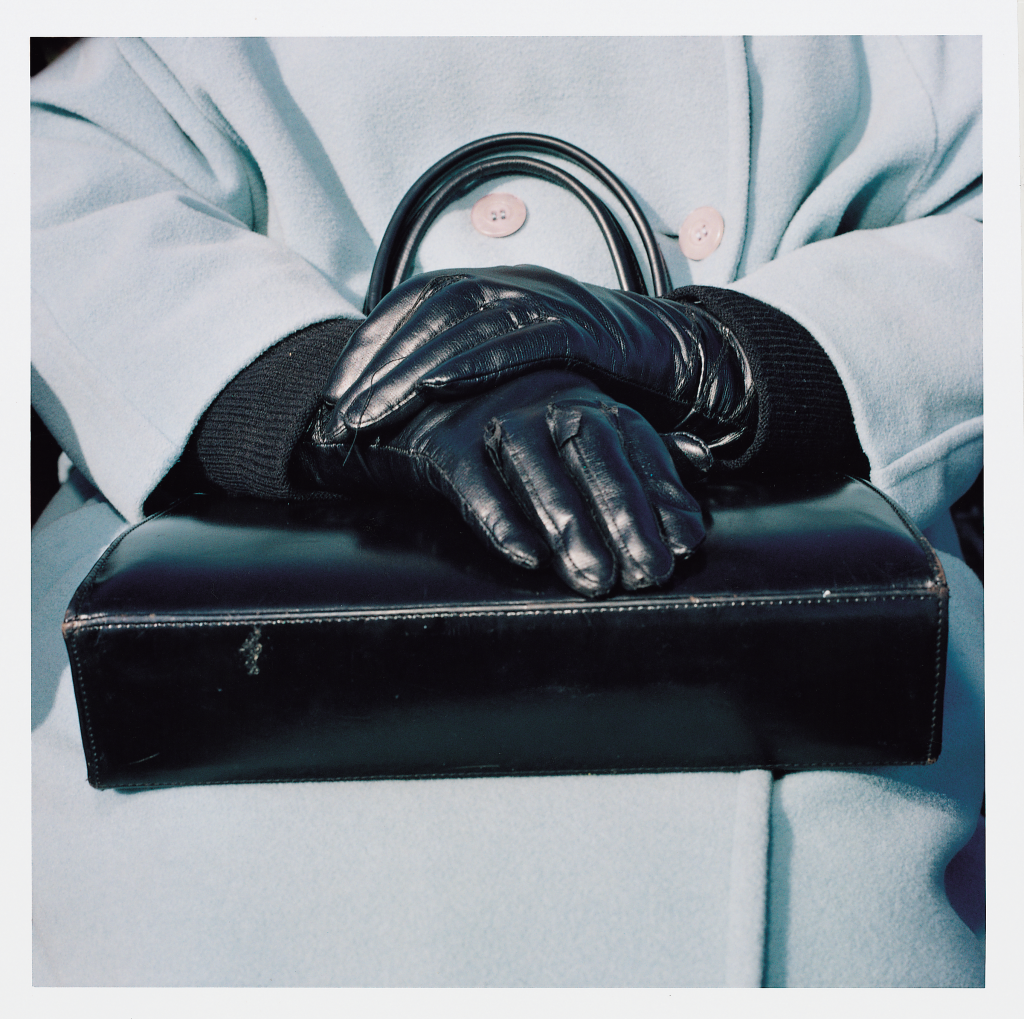

The predominance of the blue skies in these photographs propel us forward into the hopefulness that comes with being out in the sunshine and fresh air. Yet always beside us, behind us, in front of us, is our shadow. In this handbag is a dead rabbit. In popular mythology, handbags are supposed to contain everything but the kitchen sink. One image in this series – an inscrutably Thatcherite handbag held against an icy blue winter coat, may or may not contain a dead rabbit. What is important is that there exists the possibility that it does.

A version of this essay first appeared in the book Toeing The Line, published by PhotoWorks, 2000.

¹ Jane Mendelsohn, ‘I Was Amelia Earhart’, Vintage, 1997, (unpaginated)

² From the authors photographic collection

³ Martin Amis, ‘Experience’, Jonathan Cape, 2000, 63

⁴ Elizabeth David, ‘Introduction’, (writing about Secrets de la Bonne Table by Benjamin Renaudet) from French Provincial Cooking, Michael Joseph, 1960

⁵ Derek Jarman, ‘Chroma, A Book of Colour 1993’, Century, 1994, 114